The Bag: A warrior's mindset

/By Kirk Lawless

I like to tell the kids at the police academy about “The bag.” I ask them, and none seem to know what I’m talking about. They apparently weren’t issued one. They didn’t issue one to me when I was in the police academy and I thought by now it would be standard equipment. It should be.

Back in the day, you just rummaged around and found your own. I still have mine and there are many of them. They are cumbersome and everywhere.

I’m not talking about “The bag,” as in the uniform. I’m talking about the other “bag” the one every cop gets whether they want it or not, they’re enormous and plentiful. In fact, the supply is endless.

“The bag” and what goes into it, comes with a formula. Let’s say that with every call you go on during your career you receive an appropriately sized rock, or brick, or cinderblock, and that’s where “The bag” comes into play.

Every natural death you respond to is sad. The ozone in the room where the body lays has changed, you can smell it. It’s a sort of staleness, the void created by a human life snuffed out. You’ll remember that smell and you get one “brick.”

Death from illness, also sad, “two bricks.”

Accidental death, sad, “two bricks.”

Suicide, sad, tragic, and pathetic, “three bricks.”

Homicide, sad, tragic, anguish, rage and disgust washes over you, “five bricks.”

Rape/sexual assault, anger, empathy and the rage, when it kicks in, “the bricks” will flow in, in appropriate numbers commensurate with the shit you see.

When the victim is a child the sadness, tragedy, the rage is incomprehensible, and gut-wrenching, “10 to 100 bricks”

Maybe you know the victim. You factor in all the variables, grief, sorrow, and pity, “500 bricks.”

Any of the above, when the victim is a brother or sister officer, you’ll get the sadness, anger, thoughts of revenge, pity, sorrow, loss and the “bricks” will probably become cinderblocks and the weight will be measured in tons.

“Shit, my bag is full. What now?” Grab a new bag and start filling it. “The full one, what I do with that?” You can try to get rid of it, but you won’t be able to shake it. Tie a knot in it and stuff it in your locker. When that’s full, you’ll probably start taking them home (that’s where the fun starts) folks want to see what’s in the bags. They want to hear about the bricks. For me, they are private things, and it’s best not to talk about “the bags” or what’s inside. Soon the bags will be everywhere: in the garage, in the attic, in the closet, way up high, top shelf, near the old gray wool blanket reeking of mothballs that will one day be your own death.

Your heart will grow heavier, likewise the badge, heavier than when you first pinned it on. After 20 years it feels as heavy as a ¾ ton pickup truck pinned to your uniform.

You shoulder the weight as best you can. Maybe you will start to struggle with it back bent, leaning into the wind. Your legs might buckle, but you power through it. It’s hard to ask for help, so you don’t. That’s the cop way.

Every bullet hole you see or apply direct pressure to, to staunch the flow of blood, will weaken the mental dike and you keep hammering in those plugs, but as fast as you do, another leak springs, but it ain’t water, it’s blood. Gallons of it, sometimes it’s a stranger’s blood, sometimes it’s another officer’s, sometimes it’s your own.

So now you’ve got these damned bags of brick, cinderblocks, hunks of asphalt covered in blood. You start accumulating them in the attic of your mind, in your dreams, your nightmares.

In the basement of your mind, where it’s dark, that’s where you’ll put the blackest, bloodiest bags. They’re heavy and they leave a slick trail down the cellar steps, the weight of what’s inside thumping against every stair. Once hidden, you turn and run up the steps as fast as you can, because whatever was in that bag sounds as if it’s chasing you, breathing down the back of your neck, but you’re able to slam the door and throw the bolt. Whatever had been chasing you slams against the door bowing it from its frame, heaving with every inhaled and exhaled breath coming from the other side. “It” wants you, not today but maybe someday.

Shotgun suicide to the face, “Hollow head” is a frequent flyer with me. When he gets out of his bag, he’s annoying mostly. He doesn’t do much, appearing from my peripheral vision, walking quickly and steadily near the foot of my bed and coming around to my side. His hollowed head has no eyes, no ears. I can see the inside of his skull where his brain once sat, before he made an extraordinary and grisly piece of carnival “spin art” out of his head with a 12-gauge shotgun while sitting near a ceiling fan on its fastest setting.

His body language is inquisitive and with what’s left of his head nodding, neck craning from side to side trying to listen, but without ears to hear. No eyes, but straining to see. He’d like some answers, maybe some help, but for him they just aren’t coming.

Picture a locomotive, tons of steel, cannonballing down the track. No brakes, curve ahead, and beyond that a bridge, but the trestle is out. So fast, so fast, off the rails, plumes of smoke, hot ash and flames, then nothing, blackness, zero sound and waking up in a puddle of sweaty, torn sheets.

Shit, shower and shave, put on the “bag” (uniform) and head out the door to “Get back after it.”

Maybe you should talk to somebody? You might. One day. No shame in that at all. You’ll know when it’s time to do that. The older cops know. Find a good one and reach out. Chances are they will lift you up.

Roll call is over and it’s time to hit the streets. The old Sarge whispers, “Don’t forget to grab a new bag kid. I think you’re gonna need it.”

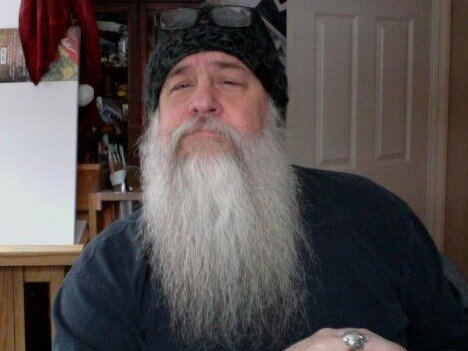

Kirk Lawless is a 28 year, decorated veteran police officer from the St Louis area. He’s a former SWAT operator, narcotics agent, homicide investigator, detective and Medal of Valor recipient. Off the job due to an up-close and personal gunfight, he now concentrates on writing. He’s a patriotic warrior, artist, poet, actor, musician, and man of peace.